Emerging from her Covid-hibernation in time for her ninetieth birthday, Rita remains a lively character. Welcomed into the world as the source of a few more union pennies during the bitter miners’ strike, Rita’s resilience no doubt owes much to her Lancashire roots. But it was events from her school-leaving weekend, aged 14, that have defined her life.

Hardy and Hospitable

Rita was raised in industrial Leigh, situated between Manchester and Liverpool. Mill life literally shaped her family. “My mam worked at a cotton mill and she lost her ring finger – at about 15 – so she wore her ring on the other hand. Like people in those days, mam never went out without hat and gloves and always tucked her ring finger in, so people didn’t notice.” During the war, Rita’s mum went to work on munitions and she had a meal at her grandma’s each day.

The classic two-up, two-down terrace the family rented was basic: “no electricity, gas lighting in the downstairs rooms with candles to light us to bed.” The family shared a yard with five other houses in the terrace – but at least by walking across it they could reach their own toilet! Most houses had an old tin bath hanging outside on a wall.

Getting a hot bath was not straightforward: “In the corner we had a boiler that you boiled clothes in that we stoked up with coal, and used it for water for the bath.” The family was blessed to rent this house: “we only lived there because when mam was young she used to look after an old gentleman and, when she married, he let them live with him.”

But the family was still very hospitable. “Our home was an open house. Mam used to say ‘what we have, they’re welcome to.’ My older sister, Irene, had a boyfriend first, from Yorkshire. We had to give our bed up for him. Dad would sleep in the chair downstairs and Irene and I would sleep with mum in the big bed.” When people came over from Europe to work in the mines with Rita’s dad, he invited them to stay with him, so eventually the family got a camp bed for them.

Wartime tragedy

Working down the mine took its toll on Rita’s father. “It was the only life he knew and, as he got older, he found it quite hard. He used to drill the holes for the detonators so he was on the real coal face. He used to come home trying to work things out; he didn’t used to talk but we knew he was worried about something.”

Rita’s brother, Ralph, ten years older than her, wanted to follow his father down the mine. But their dad said he wouldn’t take a dog down the pit, so when Ralph was called up, he chose the navy. Ralph’s frigate ended up escorting wartime food convoys between the UK and Canada. Then tragedy struck. “My brother was lost in the Battle of the Atlantic, when I was 13. We heard at first that he was missing at sea, presumed dead. I thought that he would always come back, and I used to pray that he would come back.”

Eventually archives revealed that her brother had been rescued after his ship had been torpedoed – only for the rescuing ship to be torpedoed too. This time there was no escape. Rita’s dad was the worst affected: “I often wondered if dad ever regretted his previous decisions. I used to enter the room and find him looking with tears in his eyes at the photograph of his only son.”

Growing up

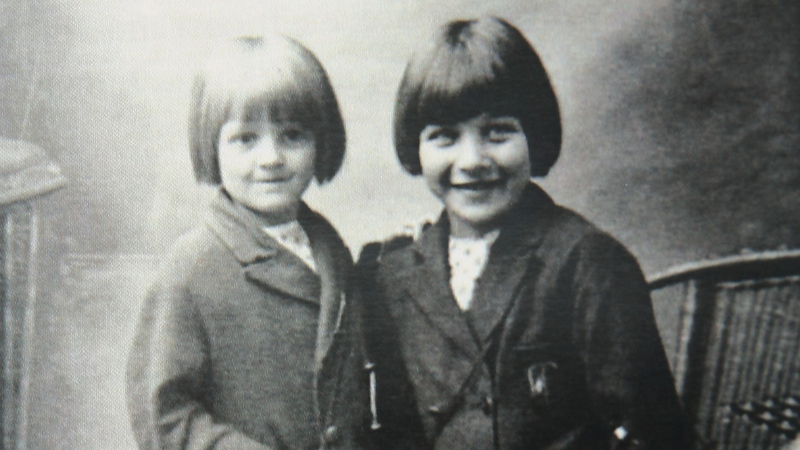

At the time of the tragedy, Rita was almost ready to leave school. She’d been there for ten years. “I started school quite early – at three – because I had a sibiling at school. We had a rest in the afternoon. They made little beds for us – hammocks hung from the legs of tables turned upside-down.”

Rita enjoyed her schooldays. “I was very small so I had to exert myself a bit – make myself known! I was quite daring. We climbed trees. My friend had a granny who lived in a farmhouse and we tried to get in without her knowing.”

After turning fourteen in August, Rita was set to leave school the next holiday – October half term – or, as it was back then, “potato picking week.” That weekend everything changed.

A memorable weekend

Rita had enjoyed “baby walking” – knocking on someone’s door and asking to take their baby for a walk in its pram. This was common then with the trust of a tight-knit community. Rita liked to wheel around baby Stephen, the son of the first minister of the Mission Hall. Although her parents didn’t attend worship themselves, they had encouraged Rita to attend the children’s meeting. Now she began attending the Sunday services regularly.

The day after Rita left school, there was a special service. It was autumn 1944 and there were lots of army and naval camps around. Some servicemen came to the mission hall to lead the service. After five years of war, including bombing raids on nearby Manchester and Liverpool, death was real and what happened next was important to know.

Rita had come to know that there was a difference between knowing about God and knowing God personally. The lives of her Christian friends were a factor. “I had been thinking about it. God had been speaking through various services. It was the influence of the Christians that made you realise that I wasn’t like them. And I had to make a decision.”

Turning point

During the special service, Rita heard again how Christ had loved her enough to die for her sins. She heard his call to turn from her sins, to seek his forgiveness and to follow him. Rita thought: “I really must become a Christian.” She recalls, “then, I thought I was making a decision to follow Jesus. It was later that I realised that it was God calling me.”

In wartime, some sought forgiveness in the face of death, but didn’t want to hand over control of their life. Rita was different. Her response to Jesus’ call at fourteen shaped everything. As she explains: “I realised my life had to change. I had to follow what the Bible said, to do the things God wanted me to do and not go my own way. I had to commit my whole life to the Lord.”

What a weekend for a fourteen year old: “I left school on the Friday, became a Christian on the Saturday and started work on the Monday.” As Rita headed off early in the morning to Courtauld’s Mill, she had a lot to think about.

If you have any questions or would like to know more please contact us.